Snapshot Press Release: "Power to the People" Interview w/ Emory Douglas

/“A picture is worth a thousand words but action is supreme.” - Emory Douglas

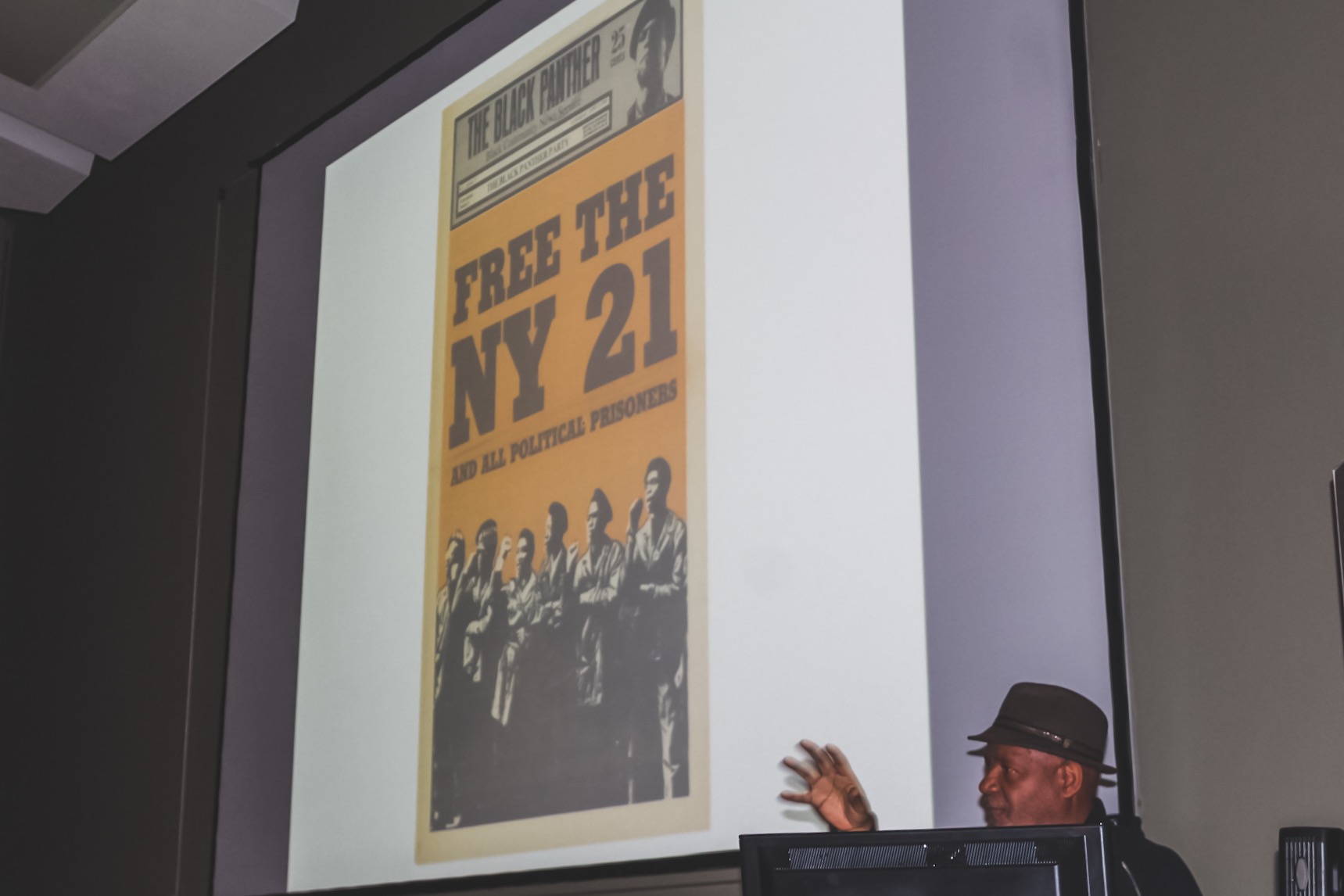

Emory Douglas, visual Revolutionary Artist and Black Panther Party icon, made his way to Milwaukee’s UWM campus Peck School of the Arts, on October 24th, to give a presentation on his extensive collection of socially critical imagery. His work within the Black Panther Party and his contribution to history have made his presence an exciting catalyst to the social narrative in which we have been discussing. CopyWrite magazine was asked by AIGA-Wisconsin and UWM to sit down with Emory, to get his take on his #SociallyResponsible artistic quest and all the other things that spread between the lines of his symbolism.

CW: “For all intents and purposes, you were the artist that drew all the images in The Black Panther newspaper?”

ED: “Ninety-nine percent. There were others who contributed but it was my responsibility to show them how to put social justice content into the artwork.”

Though we know Emory as the man behind the art, his contribution to history had to start off understanding not only the image but the purpose behind it.

ED: “Well that became my role when I . . . I would have to initially start when I was in the Black Arts Movement, transitioning into the Black Panther Party. I was attending City College of San Francisco and I was beginning to take up Commercial Art. That showed you production skills as opposed to Fine Art . . . You learn figure drawing, the printing process, design elements, all those things. While there, I was a part of the Black Arts Movement. I was also there as the Black Conscious Movement was coming about, where we began to define ourselves as Afro-American and Black opposed to being defined as Negro.”

Trying to figure out what he could do at the time to help the movement, he had been told that there was a meeting taking place where they were planning the visit of Malcolm X widow, Betty Shabazz, to the Bay Area. Emory was also asked to do a poster of Shabazz. When he went to the meeting they would also discuss security for that event. The men who would agree to be that security would soon after, change his life.

ED: “When they came, it was Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. It was after that meeting I asked them how I could join and they gave me a card . . . I eventually started calling Huey and I would catch the bus and go by his house. He would show me around the neighborhood and introduce me to folks. Then we would go by Bobby Seale’s house.”

He noted that this was all happening around early January into late February 1967. Only a few months after the initial start of the Black Panther Party in October of 1966.

Fast forwarding, Emory recalled the first issue of The Black Panther News Paper being on legal size paper, done with a typewriter, and markers. It was the editorial project of Bobby and another member known as, Elbert “Big Man” Howard. Emory noticed them working on the leaflet while convening at the Black House, where cultural events took place, and creatives like Sonia Sanchez and Ed Bullins would hang. Interesting enough, Eldridge Cleaver, who became the party’s Minister of Information, lived upstairs from the Black House and would be drafted over to help with its planning with his comprehensive writing skills.

ED: “One evening I went over there, nothing really was happening but Bobby, Huey, and Eldridge were downstairs. I saw them working on that first leaflet and I told them that maybe I could help them improve it. So I went and got my materials. I walked home and walked back, so it took me about an hour. When I got back they said, ‘Well we are finished with that. But you have been hanging around and you seem committed. We are going to start this paper and we want you to be the Revolutionary Artist.’ So that became my initial title. My job would be to tell our story from our perspective.”

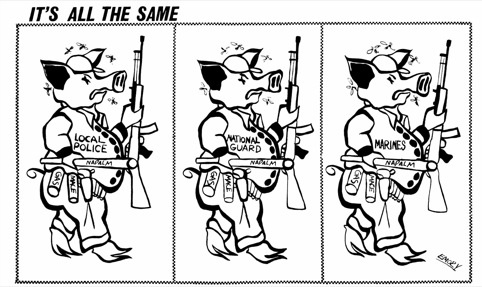

And so it began. Emory would create the first tabloid paper for the Party from the content pressed at the Sacramento legislative meeting to change the de facto gun laws, that would affect The Panthers legal use. Setting the standard for The Black Panther Newspaper that would carry on until Fall of 1980, Emory’s art would become the visual rhetoric for a cultural movement we still dote on till this day. He would even be responsible for the visual interpretation of the Police as the “Pig”.

CW: “The first time you drew the pig was that the first time that it was projected in that way towards the police?”

ED: “It had been defined like that by Huey and Bobby. But when they asked me to do the pig drawing that was the first time [it appeared in that way] . . . there was a book from maybe 100 years or so ago that somebody had that defined the pig like that . . .”

CW: “As some type of authoritative figure?”

ED: “Yes.”

Huey had original requested Emory use a clipping of a pig on all four hooves, with a police badge number of those cops who were behaving as bad actors in the community every week.

Emory & Lexi (Editor-in-Chief)

ED: “Then it just came to me one day, ‘Why don't I just stand it up on two hooves?’ ”

CW: “Oh yeah? Like how it really looks?”

Emory lit up in laughter.

ED: “Haaaaaaaaaaaa, Yea. With the flies and everything. Then it really took on a life of its own. It became an iconic symbol that transcended the African American community. It became a universal symbol.”

CW: “Now everyone is calling them the pigs!”

He chuckled softly with a glimmer in his eye. As comical as the image was, and still is, it holds a weight that is the stringent representation of the unhuman like disposition the legal forces of our country has displayed against the disenfranchised. Though creativity comes in many forms, Emory had no clue his social expression would become such a major part of revolutionary rhetoric.

Now let's be clear, the times in which Emory made his mark were times of civil unrest, political and social scrutiny, and homefront combat. It was risky. There was bloodshed and unfortunately, there were lives lost. Enduring these times takes strength, not only physically, but mentally and emotionally.

ED: “People had all kind of issues that came together, to deal with the social injustices that existed. So whatever it was that you had when you came into the party, you brought that baggage with you. We had to respond to those problems the best we could.”

But it was his next comment that dropped down on the room. Just as deep as his art could display, so would his words cut:

“You could say people were psychologically already messed up from colonization.”

Well, then . . . no argument here.

Discussing today's realities versus the past, Emory believes that today’s issues are even more trying. He marks the dynamics that generations face now are layered with environmental plight (global warming or not, polar caps are melting), corporate exploitation/investment in culture (representation is being marketed as gatekeepers to our communities authenticity), political friction (we are closer to nuclear war than ever before), and social dysfunction (police brutality is still alive and well).

ED: “As much as things change. Somethings stay the same.”

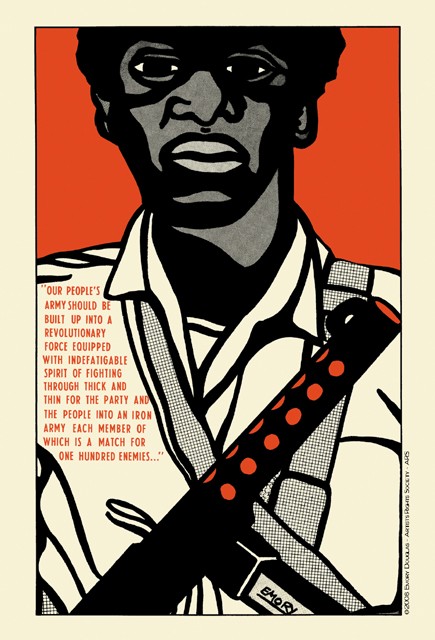

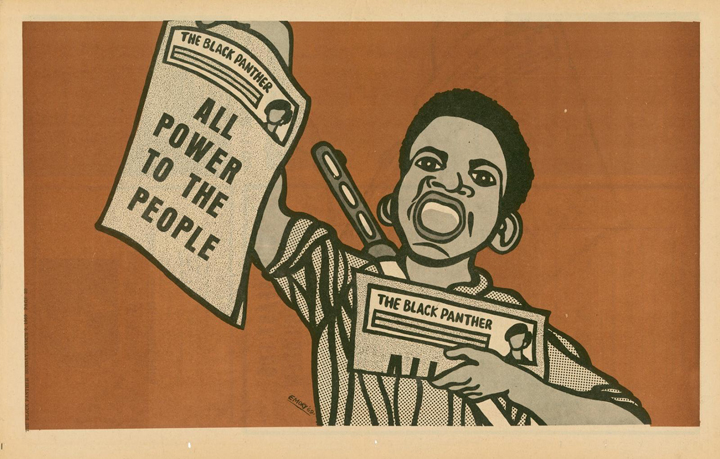

As an artist his opinions on purpose and meaning are strong. The messages that his art and many others’ creativity display are not isolated depictions, but should and have transcended cultures, classes, and even the disciplines in which they are created.

ED: “The message comes from listening to the people . . . Hearing what they are saying and their concerns, as well as your own concerns integrating, comes out in the artwork. I mean you had older Black middle-class brothers and sisters identifying with the Pig drawing just as much as you did with the people out in the streets.”

He argues that his aesthetic as an artist grew out of the awareness that needed to be displayed during that time. When questioned about the importance of visual art as a form of protest, from the time of his very controversial symbolism with the Black Panther’s till now, he reminded us that the context of his art came out of an organization backing a movement. It was not his voice alone. It was not the Black Panther Party versus the world. It was the system against the people.

images provided by: AIGA, www. journalstar.com, www.openculture.com , www.chicagoreader.com, and www.artnau.com

“We were like the nucleus or a spec of dust with a great impact. We inspired.”

CW: “Do you think without the Black Panther Party you would be the artist you are today?”

ED: “In some ways maybe, but not completely as I have developed. Because it's not only just the artwork itself but it's the collective environments. It's the criticizing and evaluation of the work and how you’ve done it. Sometimes it's in a casual way and other times it's in a real critical way.”

After the dis-assemblement of the Black Panther Party, Emory started working for the Black Press, creating imagery for their publication. Today he travels, collaborating with artist around the world to promote and produce socially conscious art that speaks on real-world issues. His mediums have even advanced beyond the production processes he learned in college so long ago, including the use of photoshop which he finds quite useful in the remixing his old compositions and his new wave artistic critic of the free world.

Throughout his lecture Emory commented on his art, its meaning, and his legacy, inspiring the room with his unyielding views. Regardless of if you agree with Emory’s position or not, his story is a reminder of the power of creativity, the communal service that can be a calling for an artist, and the impact a unified voice can make.

As we step forward in our purpose we must not forget that the revolution we call on is not a new one but the rebirth of its kind.

POWER TO THE PEOPLE.

Lexi for /CW